Timberyard: The Value of Variety

This is Timberyard, a very successfully-designed café that’s a big hit with students and other independent workers in Shoreditch. What strikes me about the places that have hit the right note with students is that incredibly wide variety of different kinds of seating, different kinds of spaces, and a thoughtful variety of configurations that acknowledges that not only do different people have different preferences, but one person generally has a variety of different needs from a space depending on their current task, mood, or circumstances.

The front of the house at Timberyard contains a modular shared couch, old suitcases that act as coffee tables, and plenty of outlets. Enough outlets for everyone.

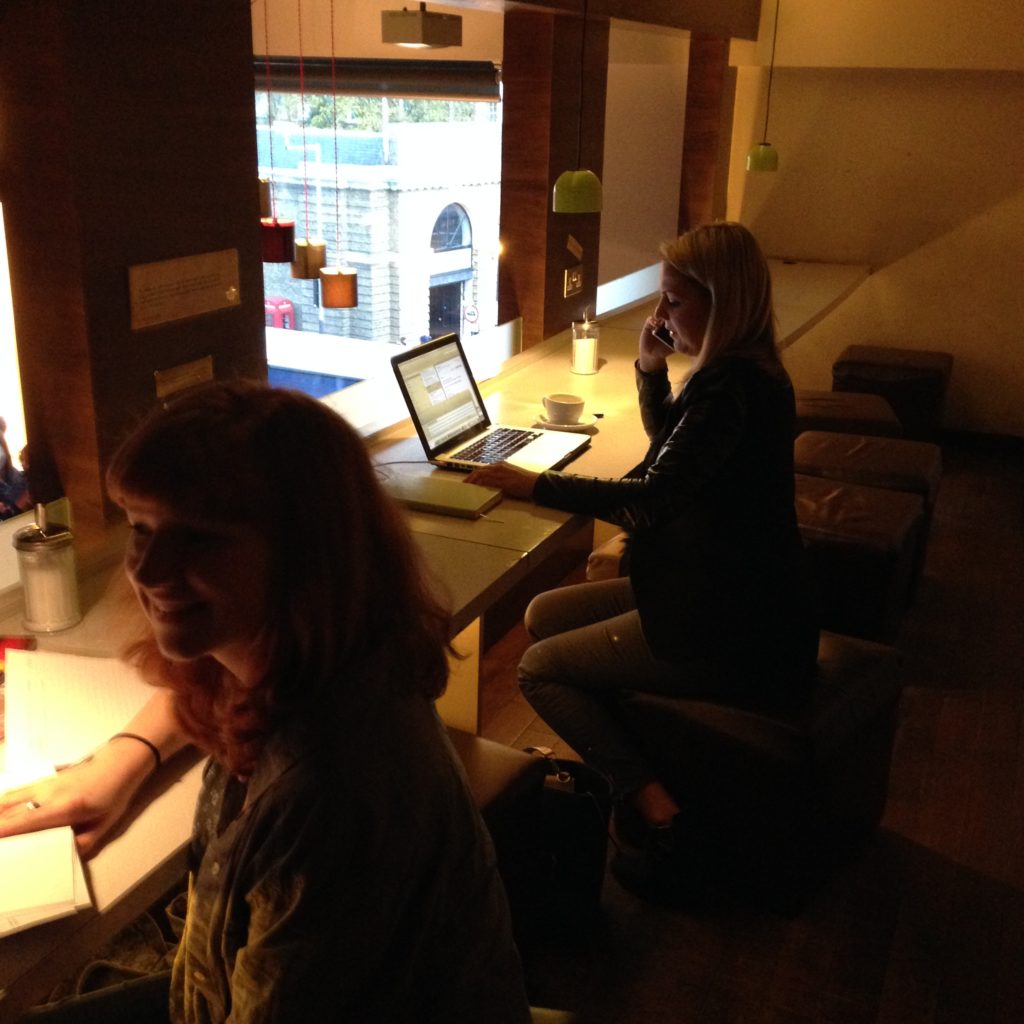

A sight I’ve become accustomed to: bar seating by the window. This kind of space is almost universally understood as individual, private space within a public space. I’ve started to notice that in libraries that don’t build spaces like this, patrons will drag a chair over to a window, face it against the window, and create it. I think this kind of seating might be the most accessible and least threatening to people entering a social space like this alone. Facing outward is a kind of message that indicates that a patron is not only not looking for a conversation, but is here on their own for a reason. Again: notice the easy access to power.

A second band of bar seating, facing the wall. It’s more space that’s comfortable and available for individuals coming in alone and intimidated by the big, shared couch. But there’s another interesting thing about this bar seating:

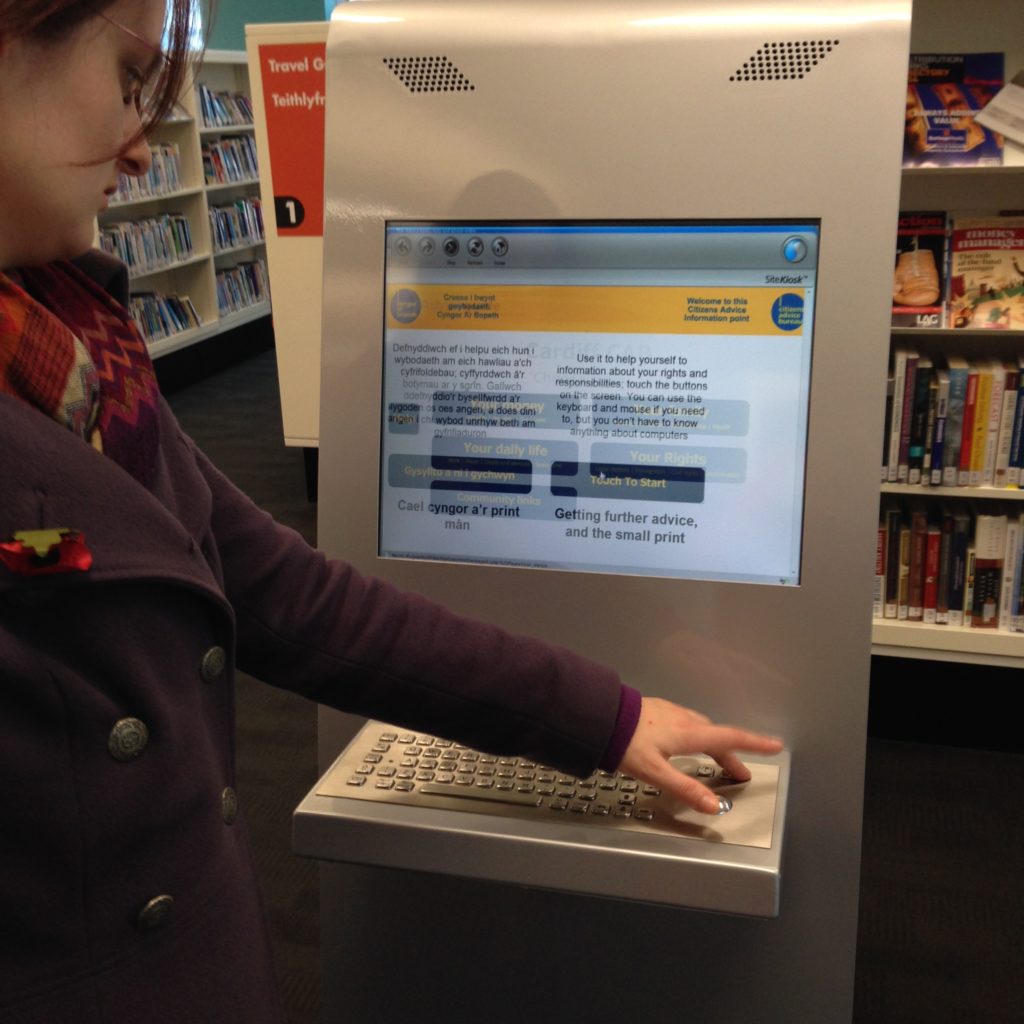

The café provides not only wifi, but ipads for the purpose or browsing the internet while drinking your coffee or having your lunch. I’ve never seen anything like this outside of a library. When I wander through our library and see how students are using our computers, a good percentage of the time I see keyboards shoved up under the monitor and a laptop or book sitting in its place. A fixed ipad like this probably isn’t a bad replacement for a catalogue terminal, when you think of it. It makes that table far more multifunctional. It’s very generous of them to provide them, really. I found three of them around the café, admittedly none of them in use.

We’ve got individual space, very much shared, common space with the couch, and also more traditional shared space for groups: three tables for four. These are small enough that they aren’t shared by strangers; these are for people who know each other, are working together, or have decided to come here together to share the space as a group.

From above, a hint of what lies below:

Downstairs, more kinds of space, all of which seems to be designed with students in mind:

Quirky, mismatched, soft seating, in a variety of different configurations! Here they’ve got armchairs you can use as an individual, or with a group. Full-sized tables that, as you can see at the back, encourages group work. This furniture can move, but it doesn’t appear to, especially. If you don’t like one configuration, this café has many more to choose from. That’s another form of flexibility, one that doesn’t require reconfigurable tables or casters.

These group spaces, filled with the noise of people talking, also includes spaces that patrons use for individual work. As we know, there are many people who don’t like to work in complete silence or solitude. Being alone in a group is more productive for them, and you can see the evidence of that in places like this.

As in most places I’ve seen, there’s also a communal table. Interestingly, in spite of all the other available spaces at Timberyard, these folks prefer to work independently together here, with ready access to power. Communal tables are tricky, and interesting: there are signals that tell patrons they can share the table, but I don’t think they’re as simple as the size of the table or the number of chairs. That factors in, certainly, but I think the affordances of the rest of the space contributes as well. If everything else is sharable in a space, a communal table will be more shareable, even if it’s thin or smaller. I wish there were a ready and easy science to this, but I’m not sure there is. I’m really fascinated by the communal table; it’s potential is so tantalizing. For me it is the definition of flexible. It can support group work, become an instant conference room, and be a place for individual work as well, all without shifting the layout at all. It can support high tech work and digital collaboration as well as work with paper and post-it notes. It’s simple, familiar, and comforting. But I think it’s also the layout most sensitive to the context of the room and the hardest to get right. I’ve seen communal tables on my travels that I suspect don’t work that well. This isn’t one of them.

Cafés in the UK are especially interesting because they don’t have much of a culture of throwing people out if they stick around too long. In that sense, they are closer to libraries than almost anything else. We also create spaces and encourage students to stick around. Because of that, I feel like we have an incredible opportunity to create really terrific spaces without worrying about turnover. I knew I wanted to look at cafés as part of this project, but I really didn’t expect the parallels to be so strong.