Space and Audio

I feel like this is a bit of a tangent, but I keep noticing these things, and I keep thinking they’re interesting. It’s my research leave, right? So I should investigate the things that strike me as worthy of observation, shouldn’t I?

The thing I keep noticing, and keep being intrigued by, is how various services and spaces make use of audio to provide critical information.

As I’ve expressed before, I’m very impressed by the signage on the London Underground. I will have to delve into this again more thoroughly, because I still find it very inspiring. The thing I immediately liked best about it was that it delivers small pieces of information to patrons exactly when they need it, and not a second before. It also works to provide “confirmation” signage, the sole purpose of which is to reassure the patron that they’re in the right place. I’m generally excited to see any acknowledgment of the emotions associated with an experience built right into the placement and content of signage; fear is always a key factor, in public transit as in library services. With the pressure to keep people moving along platforms, through long tunnels and up stairs in crowded and busy tube stations, it makes sense that the London Underground would place so much emphasis on answering patron questions exactly in the places where those questions get asked so that no one has to stop, block traffic, and figure out whether to turn right or left.

That’s not the end of the information-giving. Once on the train itself, there are maps on the walls of the entire line, so you can watch your progress. There are digital signs telling you where you are and where you’re going. This is surely enough, but on top of all this, there’s a voice that tells you where you are, which stop is next, where the train terminates, and, famously, to mind the gap.

It’s overkill, surely. I can see the map, I can see the station names on the walls of the stations as they appear, I can see it on the digital sign. Is it there purely for those with visual impairments? Possibly. But it also infuses the space with very reassuring information that’s frankly easy to ignore if you don’t need it, and easy to cling on to otherwise. Even if I know where I’m going, it marks my progress and punctuates a relatively dark journey with no real views (most of the time). It supports the written information and pins it not in space, but in time.

I’m a fan of Westminster chimes. I grew up with them; my parents had (and still have) a mantel clock that chimes every fifteen minutes, day and night. Lots of people find that horrifying, but I don’t. It’s reassuring to me. I don’t especially trust my internal clock; sometimes three minutes feels like ten, and an hour feels like five minutes. When you wake up in the night you feel like you’ve been lying there awake for hours. But the Westminster chime grounds you in reality: I’ve only heard it go off once since I’ve been awake, so I’ve only been awake for fifteen minutes, tops. I like how the chime infuses space with the knowledge of how time is passing. The sound changes from chime to chime; you can tell from the chime which part of the hour you’re in. It’s an audio version of a physical object. It’s an ancient means of providing ambient information.

I think the voice on the tube is similar. It’s providing me with ambient knowledge that I can half ignore.

There was a documentary, or news piece some time ago, about the unlock sound on an iPhone. The sound is gone from OS7, but until recently, there was a very specific, very metallic sound always accompanied the action. You can’t feel it unlocking, since an iPhone uses only software keys. But there had to be a sound so we could understand what was happening, and to be assured the action was successful. In place of a sensation, a sound for reassurance. A sound to make a digital action feel real.

Libraries are generally aiming to be silent spaces. Having things announced is a nuisance to most people. I think it’s possible that audio cues have a place in the good functioning of a library; it’s just a matter of being supremely thoughtful about it and determining what kinds of ambient information is valuable to patrons, and what kinds of audio cues would be comforting rather than annoying. There’s also the question of placement; there are no voices telling me things when I’m walking through tunnels and following signs, but there are when I’m heading up an escalator, or sitting inside a train waiting for the right moment to head for the door.

My parents have been visiting me for the last few days, so we went on a few city tours on open-topped double-decker buses. I seem to recall seeing these kinds of buses drive past me, with a tour guide shouting into a microphone. Those days are gone. Now they give you cheap earphones, and you plug into the bus to hear a pre-recorded tour in the language of your choice.

This struck me as kind of genius. The pre-recorded tour told me stories and history about the places I was looking at; it wasn’t ambient information, it was a packaged lecture based on my choice of language and volume, and the location of the vehicle I was sitting in. Initially I assumed it was hooked up with GPS so that it would play based very specifically on location, but I discovered when we got cold and came inside the bus that the driver was pressing a button to advance the script. I found that oddly disappointing. I liked the idea of a system tracking traffic and our location and giving me stories based on it. It’s a shared experience, but it’s personal. It’s utterly silent to the people around you, but immensely informative for the people listening. It’s carefully planned and thought out, and no piece of the story is forgotten. The recorded tour goes on all day, and you can jump on and off the bus where you like. That means you can listen to the tour over and over again and pick up the things you missed without asking a human tour guide to be at your disposal. That got me thinking too. How can we help pace information to keep it in line with the place a patron finds herself?

I’ve seen similar things on a different and more self-driven scale. The Murmur project in Toronto placed ear-shaped signs all over to Toronto with phone numbers on them which played stories about that spot to the caller. We can do better than that now with QR codes or just URLs, since smart phones have become so ubiquitous.

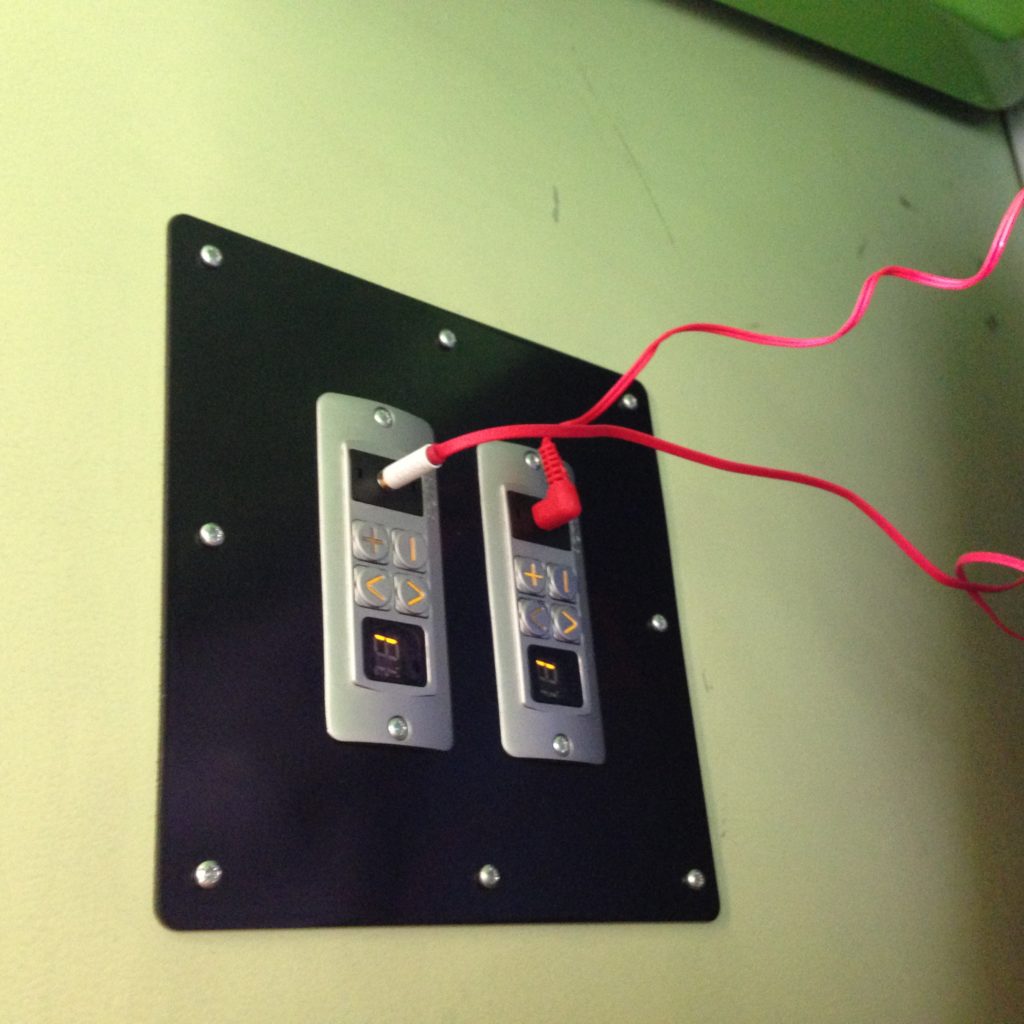

One of the very best examples of audio in libraries I’ve seen is the pre-recorded audio push-cubes in the Rama public library. You know those teddy bears with audio buttons in their hands? Or cards with audio that plays when you open them? You can buy those devices empty now, with 20 to 200 seconds of space for audio. They’re cheap, and they’re even reusable. In an effort to expose children to the Ojibwe language in order to preserve it, the brilliant Sherry Lawson of the Rama Nation uses the cubes to record words and phrases, and places them in relevant areas in her library. A patron can approach an object, see it’s written Ojibwe name, then press the cube to hear it spoken. She is providing ambient exposure to the children of the reservation by inserting her voice and her language in places where they can easily interact with it.

Perhaps it’s Mike Ridley’s fault for introducing me to the concept of a post-literate world, but there’s something about getting audio information in situ that really appeals to me. Where it provides new information, I think it’s fascinating, letting people lift up the dog ear on a place and see a whole new world underneath. Where it focuses on reassurance, I think it provides a critical service in allowing people to feel found and safe. This is technology that isn’t infrastructure; it’s a bolt on, an ambient addition, and a simple and cheap one at that. Letting audio form a feeling: that’s the kicker, for me.