The Technology Trifecta

I work with the soft side of technology. I don’t write code (I only have the tiniest bit of coding ability, and I haven’t used it in years), I don’t do hardware. I don’t monitor servers. The soft side of technology is all about working with the people trying to use it, and helping them to understand it. I’ve come to believe that there are three key things required to help other people use technology effectively. I’ve come to this realization as part of the rethink and reworking of our faculty training program this year, and it’s forced me to think about the whole experience from another angle.

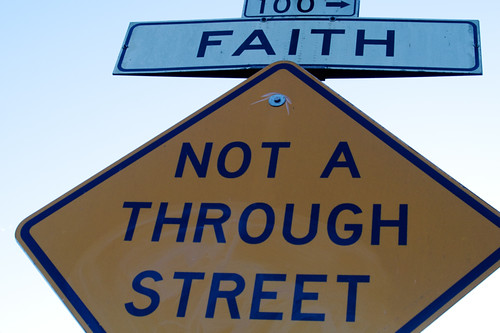

Granted, my background in theological studies and my penchant for writing fiction in my spare time probably play a role in my perspective on this, but I’m going to run with it.

The (soft side) Technology Trifecta

1. A Good Metaphor

All technology requires a good metaphor, something people can seize onto. The wrong metaphor can leave a technology languishing for ages. Metaphor is how the brain learns what to do with a thing. When they called it “email” (a stroke of genius) everyone knew what they could do with this network messaging system: send and receive, store, forward, add attachments. That metaphor is what, I believe, makes email the most obvious and easiest-to-learn application we’ve got. Blogs had a good one with old school journaling and diaries (and explains why the first run of blogs were all intensely personal). Without decent metaphors, our patrons will struggle with the web. A good metaphor might take years to think up, and we might only come up with one really good metaphor in our lifetimes, but I think coming up with them is a worthy pursuit.

2. Faith

I had the experience recently of having to investigate something pretty dire, and then relay my findings back to a distressed and disconcerted instructor. He had to take my word for it that the thing he was afraid had happened had not in fact happened. I had to reassure him that he could still trust the system. If you don’t have faith in the system you’re using, if you think it’s possible that, without your knowledge or understanding, it’s revealing secrets or displaying your content to the world without your permission, your willingness to be creative with it will rapidly vanish.

There’s a difference, however, between selling someone a system and helping them to have faith in it. You don’t have to adore a bit of software in order to have faith in it. You need to know that when you trust it with information it will do what you expect it to with that information. Setting those expectations appropriately helps people develop faith in a system. I see my role not as making you love the institutional system, but to have faith in it.

The best gift I could receive in this situation is to have the instructor believe me when I explain what’s happened. I want him to have faith in me, too. (He did.)

3. A Mac Friend

This one takes a bit of explaining. Back in the 90s when I first started using macs, I wasn’t comfortable making that decision on my own. Everyone I knew was a PC user: what if I ran into a problem? There were no mac stores then. I would have been on my own. I might not have stayed a mac user if it had not been for the one guy I knew who used macs. I had my mac friend, and I knew he could help me with the things I didn’t understand. Knowing I had a mac friend meant I could try things and feel comfortable knowing there was someone I could turn to.

In a meeting several months ago, a retiring librarian told me she wanted to switch to a mac but wasn’t sure she knew what she was doing. I said to her, “It’s okay. I’ll be your mac friend.” That was when I realized that I didn’t need a mac friend anymore. But I had become one for other people.

Of course, this is the genius of the apple genius bar: they sell mac friends.

I think every technology needs a mac friend, and that’s how I’m currently framing faculty technology support. They may not need you to walk them through every “click here” and array of options. They may just need your help to get them started, and your reassurance that you are there for them when they hit a wall. They have a mac friend; they can try things and not be afraid of having to dig themselves back out on their own. It’s like a safety net; personal, one-on-one, on call reassurance.

We’ve spent years focusing on the content of training when it comes to technology, not realizing that the most important thing we were doing while giving that training was just demonstrating that we know what we’re doing and we’re here to help.

So that’s what I’m focusing on now. I know what I’m doing, you can trust me. I’m here to help you, not just now, but all year long. See this thing? It thinks its an archive. Go play with it. If you run into trouble, I’m always here to help.