Devices, the Tube, and the Heath

The purpose of this research leave is to look at the relationship between computing technology and space, and how those two things together either support or discourage people’s goals, creativity, and collaboration. I could do this pretty narrowly, and given that I only have six months, I probably should, but I can’t help but notice the use of technology is all kinds of spaces, planned or otherwise.

There is an advantage to being away from home in this respect; you look at everything as a visitor, and being foreign opens your eyes to things you might not have thought remarkable otherwise.

It will come as no surprise to anyone that computing technology is everywhere. We have always been careful when we use words like “everywhere” and “everyone”, because not everyone had a laptop/tablet/phone, and there is that danger of marginalizing people and not taking account of the so called digital divide. Of course there are always outliers, but we’re very quickly approaching the point where we can say, without real apology, that everyone has some kind of computing device with them in all kinds of unlikely places. UTM Library’s wireless connection information cross-referenced with its headcounts and traffic data indicates that there are twice as many internet-connected wireless devices in the building than there are human beings. Computing devices are reaching a significant level of ubiquity, and it seems to me it would be foolish to start a project talking about computing and space without acknowledging that. Patrons come into libraries with devices, and I think we’ve reached the point where it’s safe to design spaces and services on the assumption that they will.

Devices are everywhere, and there are more and more kinds, shapes, sizes, and price points. And people love them. Is love the right word? Depend on them, at least. They serve as entertainment, communication media, navigation devices, and aids in preventing unwanted conversation or eye contact. They are calendars, email devices, music players, GPS units, books, and our entry into conversations with everyone we know.

It’s neither a surprise nor a revelation that there are always many devices on the tube.The fellow in the background reading the paper has a lot in common with the fellow sitting next to me reading a script. There’s a continuity there that makes brand new technologies slip very easily into this space; it’s a space where you need something to do to pass the time.

The tube is transportation, obviously, but more specifically it’s a waiting room. It’s a thin room where people wait until the doors open onto a place they need to be. It’s a space where people have to be, and congregate in large numbers. Complete strangers sit next to each other. The tube is often cramped, hot, and sometimes stalled. It’s a requirement of every day life, a habit that quickly loses any sense of wonder, novelty, or interest. London’s underground is a Victorian creation, certainly not designed for computing technology. And yet: if you want to take a photo of someone using a tablet or a phone, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better place.

As much as I’m interested in how we can design spaces that allow patrons to use technologies better, more freely, and more creatively, I have to start out by acknowledging that they will do so regardless of the design of the spaces.

Sometimes they’re barely designed at all.

This is Hampstead Heath. It’s a thousand-year-old, 790 acre park in North London, perched on its highest hills, looking down over the sprawling expanse of the city. Since the weather has been exceptionally mild since I arrived (I credit my sunny disposition for this, you’re welcome, London), it was hard to resist a traipse through it in the late afternoon. I quickly discovered that the Heath is well-supplied with 3G, because quite a number of people had their phones out. Chatting, checking email, or, if you’re me, snapping photos and sending them to your dad while carrying on a text conversation with him.

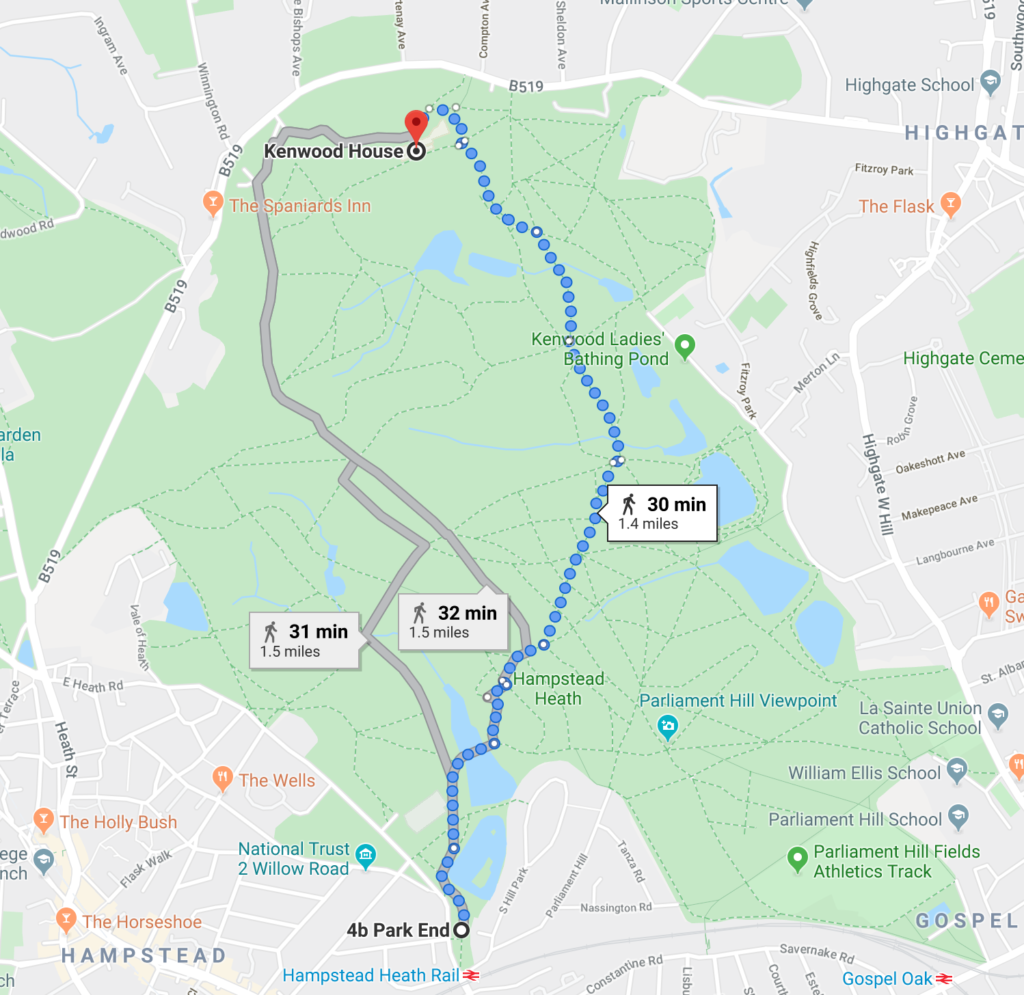

Even here, in this ancient green space, technology intrudes. Or accompanies, if we want to avoid the value judgement. Places like this can be a respite from the relentless speed of communication technology, the constant pressure to be paying attention, communicating, answering every call and question. It’s a breath of air in the middle of a busy, noisy, cramped city. But as I said, the Heath is 790 acres. It’s hilly and twisty. It joins Hampstead and Highgate, Golders Hill in the north to Gospel Oak in the south. It’s quite easy to get lost in there. It’s not a bad thing, really, to be able to reach into space and ping a satellite to help you find your way through it.

The paths inside the Heath are helpfully marked on Google Maps, and with the help of that 3G coverage, GPS will pinpoint precisely where on the Heath you are. You can use the device in your pocket not to distract you from the beauty of the Heath, but capture it, share it, discuss it, and help you navigate your way through it.

The model of the computer workstation has been at the forefront of our planning for technology use in libraries. It’s our core metaphor: everywhere you look, anywhere we think someone might need information, we insert a workstation. But our technology culture is changing fast. Spaces that were never designed for technology are becoming the perfect, most natural places for it. As computing devices get smaller, faster, and easier to integrate with the real world outside of a desk chair and a monitor, all spaces have the potential to become technology-rich, collaborative spaces.

0 thoughts on “Devices, the Tube, and the Heath”

Research leave blog post #1: http://t.co/hGhLVJWDNT the Tube, and the Heath.